The Mound of the Hostages, Tara

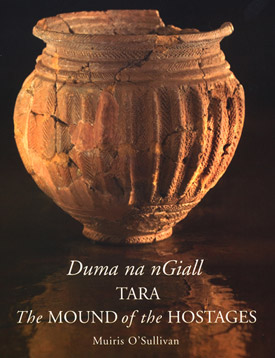

Dumha na nGiall: The Mound of the Hostages, Tara by Muiris O'Sullivan.

Dumha na nGiall: The Mound of the Hostages, Tara by Muiris O'Sullivan.

Report on the archaeological excavations carried out at the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

This is a report on the archaeological excavations at the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland. The excavations were directed initially by Seán P Ó Ríordáin, who spent two summers at the site (1955 and 1956), and were completed in a third season during the summer of 1959 by Ruaidhrí de Valera, Ó Ríordáin's successor as Professor of Archaeology in University College Dublin.

Extract from the Introduction

The Mound of the Hostages (Dumha na nGiall) is situated near the summit of the Hill of Tara, Country Meath. Its name derives from medieval topographical lore linking it with the deeds of the legendary proto-historical royal personage Cormac Mac Airt, but archaeological excavations in the 1950s revealed it to be a megalithic tomb. The tomb itself and three distinctive pre-cairn cists built against the outside of the tomb walls contained the bones of several hundred individuals who lived in the Neolithic period. Further deposits of human bone from the same period were placed in the ground around the cairn.Another intense phase of burial occurred in the early Bronze Age, both within the tomb and in the overlying mound. Accompanying these Neolithic and early Bronze Age bones was a rich assemblage of artefacts, including some spectacular objects. Traces of pre-passage tomb activity as well as late Bronze Age, Iron Age and post-medieval features in the vicinity of the mound emphasise the enduring significance of the place.

In spite of the delay since the excavations the site has yielded a comprehensive array of radiocarbon determinations, processed in 2001. The individual results are cited throughout the report in conjunction with the features to which they refer. In addition, the chronology of the site is discussed in detail in the 'Synthesis and conclusions' chapter based on a combination of stratigraphical analysis, radiocarbon determinations and diagnostic archaeological features.

Although some results from the investigations have found their way into the archaeological literature over the years, there has been no comprehensive report on the excavations until now. In any case, some of what has been written about the archaeology of the site, especially at second hand, is misleading, incomplete and occasionally inaccurate. The information presented here may help to set the record straight and, more importantly, provide researchers with a reasonably comprehensive record of the excavation, a catalogue of the material recovered and a basic interpretation of the findings.

Setting

The Hill of Tara, although rising to no more than 155m above sea-level, commands a panoramic view over the surrounding countryside, especially to the west, where the central plain of Ireland stretches to the mountains on the distant horizon. Although not visible from Tara, the Boyne River, on its northerly course towards Navan, flows through the low ground a few kilometres to the west. The most obvious landmark on the east side is the Hill of Skryne, some 3km away, to the northeast the Hill of Slane is visible in the distance.The geology, soils and drainage of the area have been summarised by Fenwick (1997). Lower Carboniferous limestone is the principal underlying rock, but sandstones and mudstones can also be found locally. The topography of rounded hills, of which Tara itself is an example, reflects glacial activity during the Pleistocene, and there are deposits of glacial debris in the valleys. Grey-brown podzolics forming productive farmland are the dominant soil types in the neighbourhood. The Hill of Tara itself is a limestone ridge about 2km in length. It is drained to the west and north-west by the Skane River system, part of the catchment of the River Boyne. About 9km northwest of Tara the Boyne is augmented by the Blackwater at the town of Navan and veers east towards Slane and the great Boyne Valley complex beyond, before entering the sea near Drogheda. This river system acts as a geographical thread linking Tara with the Boyne Valley passage tombs on the one hand and the Loughcrew complex on the other. Although applicable to the late prehistoric era at the earliest, it is nevertheless interesting that early written mythology invests the Boyne in particular with rich symbolic significance, and it is possible that the roots of this sacredness may lead all the way back to the Stone Age.

Tara has long been associated with the Irish Iron Age, being one of the great royal sites of the proto-historical era. The excavations of the 1950s, however, demonstrated that not all of the monuments could be presumed automatically to belong to the late prehistoric period. In recent decades there has generally been a greater appreciation of the time-depth represented at Tara, reinforced by the discovery of Neolithic and late Bronze Age elements at comparable complexes such as Dun Ailinne and Emain Macha. The suggestion that the so-called Banqueting Hall (Tech Midchuarta) of the medieval imagination may be a cursus monument of the Neolithic period is particularly interesting here because this earthwork appears to be aligned towards the Mound of the Hostages, the intervening Rath of the Synods (Ráith na Senad) being a later addition.

Since the early 1990s the Hill of Tara has been the focus of a concerted research scheme under the auspices of the Discovery Programme. A detailed survey of the complex has been published (Newman 1997) and further geophysical survey has occurred in the meantime (Fenwick and Newman 2002). This programme, further illuminated by Bhreathnach's historical research (1995), has provided the most comprehensive account to date of the archaeological remains at Tara. Apart from clarifying aspects of the previously known earthworks, the geophysical surveys have revealed evidence of intriguing and previously unknown subsurface features, most notably a second great oval enclosure intersecting Ráith na Ríg and apparently centred somewhere within Ráith na Senad. The Mound of the Hostages is the only upstanding monument enclosed within both great oval enclosures. In the course of the current volume the geophysical findings will be discussed in the context of the features revealed in the excavations. A recent re-excavation of the ditch of Ráith na Ríg close to the Mound of the Hostages will also be discussed.

Hill of Tara, Mound of the Hostages after removal of the earthen mound in 1959

Review by Chris Scarre - Durham University

We have repeatedly been exhorted in recent years to view Neolithic monuments not as static artefacts but more as works in progress, subject to successive remodelling and renegotiations of meaning and significance. Such monuments were also, from their first foundation, powerful sites of memory. There can be no better illustration of these two precepts than the Mound of the Hostages at Tara.Tara has long been well-known as the famous royal centre of the proto-historic period. The Mound of the Hostages (Dumha na nGiall) owes its name to 19th century scholars who sought to identify visible monuments with places mentioned in 11th century manuscripts, associated with shadowy historical characters and events. In fact, as the excavations reported here revealed, the Mound of the Hostages proved to be several millennia older than this, and is indeed the earliest of the major monuments on the Hill of Tara. The character and age of the monument were, however, entirely unknown until Seán P. Ó Ríordáin, Professor of Celtic Archaeology at University College Dublin, began excavations in 1955 and identified it as a passage tomb.

The Mound of the Hostages has featured prominently in subsequent discussions of Irish chambered tombs, not least for the abundance of the human remains recovered from the chamber, and the complexity of Neolithic cremations and inhumations within and around the mound. Yet despite a number of preliminary reports, the full account has had to wait for almost half a century. The circumstances of the excavation itself were tinged with sadness. Ó Ríordáin had planned three seasons, and began work in 1955 but fell ill and died before the third season could be completed. The baton was passed to his successor at Dublin, Ruaidhrí De Valera, who directed the projected third season in 1959. Thirty years later, Muiris O'Sullivan assumed the major task of seeing the final report through to publication. The result is a volume which reads partly as a window back into the 1950s, partly as testimony to the perseverance of O'Sullivan and his team in working through site notebooks, boxes of finds and specialist reports to produce a coherent account. Above all, however, in the author's own words, 'it is a tribute to the careful excavation techniques and record-keeping of the field-workers that so much information can still be retrieved from their findings.'

The core of the volume consists of three chapters that take us through the key components of the site: features beneath and around the mound; the megalithic tomb and its associated cists; and the covering cairn and mound.

A hint of Mesolithic presence is furnished by a single Mesolithic flake, and there is slight evidence of early Neolithic activity in the form of radiocarbon dates on charcoal beneath the mounds (plus some sherds of possibly early 4th millennium pottery) but activity begins in earnest during the second half of the millennium with the construction of the passage tomb. This was covered by a stone cairn which in turn was capped by a clay mound. Unlike other Irish passage tombs, neither cairn nor mound were edged by an orthostatic kerb, but the monument was encircled by a series of cremation deposits lying outside the edge of the cairn, many of them within small settings of schist slabs. The chamber itself conformed to the tripartite plan characteristic of many Irish tombs but was remarkable in two particular respects: in the numbers of individuals represented (a total of around 200, both cremations and inhumations); and in the presence, against the rear of the orthostats, of stone-built cists containing a further 63 or more individuals.

The excavation and interpretation of these chamber deposits was considerably complicated by the presence of Early Bronze Age burials accompanied by Food Vessels: for example, two successive crouched inhumations had been made in a pit dug into the Neolithic cremation deposit in the inner compartment of the tomb. A further series of Early Bronze Age burials had been inserted into the clay mound overlying the stone cairn. A small difference between the dates for Bronze Age burials in the chamber (four dates 2281-1943 BC) and in the mound (fourteen dates 2131-1533 BC) lead the authors to suggest that the burials in the mound may have begun only when the chamber itself was considered to be full. (One small note of criticism here is that the calibrated dates are quoted with 1-sigma intervals, although the 2-sigma intervals are provided in appendix 7). Also from this period are some 30 fire pits around the base of the cairn, which may have been 'a sanctifying ritual associated with the expansion of burial activity from the tomb interior to the mound.'

Two features of this sequence are especially interesting. The first is the complexity and chronology of the Neolithic funerary activity in and around the chambered mound. The three cists at the back of the orthostats are built within the bedding trench that had been cut into the bedrock to receive the orthostats. They were sealed once the covering cairn was built. At the same time, dates from the cists, from a sample of bone in the orthostat bedding trench, and from Neolithic material within the chamber itself were contemporary. This appears to indicate what has often been suggested but can rarely be demonstrated, that the tomb chamber initially functioned as free-standing funerary structure before the cairn was built around and above it.

The second feature of special interest is the rhythm of activity on the site. The authors suggest that the Hill of Tara 'may already have been a place to visit before the Neolithic' but what is particularly notable is the apparent lull in activity between the last Neolithic deposits in the tomb chamber (c. 2900 BC) and the renewal of interest in the Early Bronze Age, some six or seven centuries later, when a dozen or so burials were inserted in the chamber and a further twenty or more in the covering mound. What happened during these centuries? Did Tara lose some of its importance for a while, or did activity switch to another area on the hill?

Another interesting suggestion is the possibility that the clay mound might have been added during the Early Bronze Age specifically to allow the insertion of additional burials. The original excavators rejected the idea because there was no evidence of slippage around the edge of the stone cairn, such as might be expected had it been left exposed for several centuries before the clay capping was added. Yet the case is not conclusive and the possibility remains open that the Mound of the Hostages was significantly altered during the Early Bronze Age by the addition of an outer envelope. It is certainly clear that the ring of Early Bronze Age fire pits encircles the foot of the clay mound fairly tightly.

As these comments make clear, the detail included in this volume allows the unusual nature of the passage tomb and the complex sequence of constructional and depositional events to be studied in some depth. Certain previously published conclusions, such as the total number of Bronze Age burials in the mound, are revised. The confused stratigraphy, especially within the chamber, has been greatly clarified by 58 radiocarbon dates (both conventional and AMS) run at the Groningen laboratory. In sum, this volume enables the Mound of the Hostages to take its rightful place as one of the key sites for the understanding of Irish passage tombs, and to shake off the cloud under which it has languished for the past 50 years.

The book is also a pleasure to use. Coloured diagrams allow the complex phasing of the site to be followed with exemplary clarity, and key finds, too, are illustrated in a series of colour plates. It is all the more regrettable, given this generally high standard of production, that the key cross-sections (pp.12-13) and overall site plan (pp. 24-25) are so tightly bound into the gutter that they are largely unusable. Against this, however, must be balanced the wealth of photos from the original excavations that are reproduced here, and make this not only a key excavation report but also a fascinating historical document.

Chris Scarre - Durham University October 2006

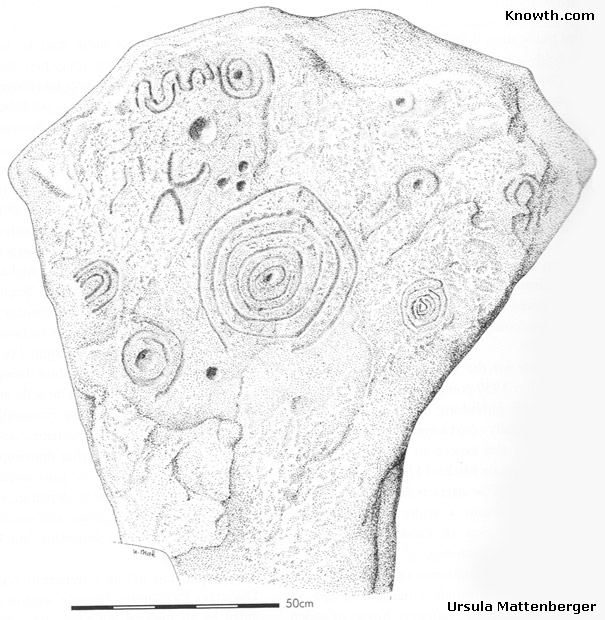

Drawing of decorated stone, orthostat L2, Mound of the Hostages by Ursula Mattenberger from the book Dumha na nGiall (The Mound of the Hostages), Tara.

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Newgrange

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Hill of Tara

| Fourknocks

| Loughcrew

| More Places

| Labyrinths

| Local Info

| Art Works

| Articles

| Images

| Books

| Links

| Boyne Valley Tours

| Contact