The Mound of the Hostages, Tara

Duma na nGiall - The Mound of the Hostages, Tara by Muiris O'Sullivan.

Duma na nGiall - The Mound of the Hostages, Tara by Muiris O'Sullivan.

Report on the archaeological excavations carried out at the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

This is a report on the archaeological excavations at the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland. The excavations were directed initially by Seán P. Ó Ríordáin, who spent two summers at the site (1955 and 1956), and were completed in a third season during the summer of 1959 by Ruaidhrí de Valera, O Riordain's successor as Professor of Archaeology in University College Dublin.

This report incorporates their findings, supported by post-excavation analysis. The earliest features recorded at the site date from about the mid-fourth millennium (cal.) BC and include the remains of individual fires, spreads of charcoal and a ditch running partially underneath the cairn. The mound itself is a mantle of soil, approximately 1m deep, covering the cairn which encloses a passage tomb.

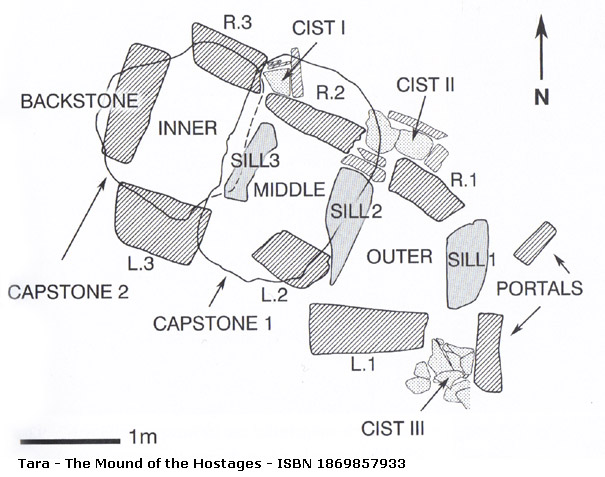

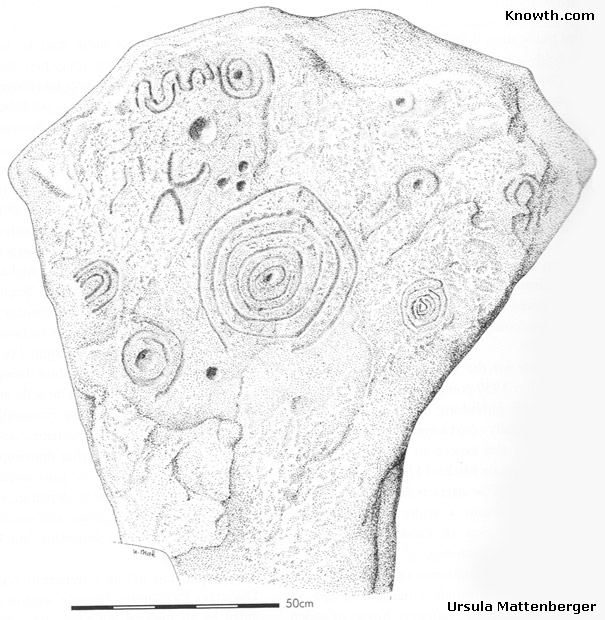

The tomb consists of three successive compartments separated by low sill stones, the roof stones surviving over the two inner compartments. Noteworthy features of the tomb include the occurrence of megalithic art on two of the orthostats, the presence of three cist-like structures against the outer faces of the orthostats, and most remarkably the collection of burnt and unburnt human bone representing hundreds of individuals distributed throughout the tomb and cists, accompanied by a rich array of artefacts, some of which are decorated.

Surrounding the cairn and sometimes located beneath the earthen mantle, the excavators recorded a ring of seventeen bone deposits that, like the earliest dated burials in the tomb, have produced radiocarbon determinations focusing in the period 3350-3100 (cal.) BC. A ring of fire pits coinciding spatially with the ring of burials has been radiocarbon dated to more than a millennium later.

Within the tomb the Neolithic deposits were disturbed as successive Early Bronze Age burials were incorporated, and in due course the burial activity spread out into the overlying mound so that approximately nineteen separate burials occurred in the earthen mantle, some of them accompanied by richly decorated pottery and other artefacts. Traces of linear palisades located close to the mound appear to date from about 2500 (cal.) BC. Later features include a Late Bronze Age ring-ditch located beside the mound, a small number of Iron Age finds and some post-medieval elements.

Plan of megalithic tomb (Mound of the Hostages)

Carrowkeel pots from the pre-cairn cists at the Mound of the Hostages

Duma na nGiall: The Mound of the Hostages, Tara

Book review by Elizabeth Shee TwohigIn 1952, Seán P. Ó Ríordáin, Professor of Celtic Archaeology at UCD, began excavations at Tara and in 1955 and 1956 he excavated at the most prominent mound on the hilltop, known as the Mound of the Hostages. He found that the mound covered a small passage tomb, facing southeast, which was covered by a stone cairn, with an overlying clay mantle. Sadly, Seán P. Ó Ríordáin fell ill, and died in 1957. His successor at UCD, Ruaidhrí de Valera, completed the excavations in 1959.

The author of the volume under review, UCD lecturer Dr Muiris O'Sullivan, has been working intermittently since the late 1980s on the excavation report and has now seen it though to publication, 50 years after the excavation commenced. In the intervening years, other UCD archaeologists worked on aspects of the material, notably Prof. Michael Herity (Neolithic artefacts) and Dr Rhoda Kavanagh (Bronze Age pottery and knives).

One of the strong points of this excavation report is the suite of 58 radiocarbon dates that were processed in Groningen in 2001; these are presented and analysed here by A.L. Brindley, J.N. Lanting and J. van der Plicht. These dates have contributed hugely towards one's understanding of the sequence of events at the site. Both regular and AMS dating were used as appropriate (AMS of necessity for cremated bone, and also for the unburnt bone, to avoid destruction of large quantities of it in advance of any further anatomical research); note however that the caption for the list of dates in Table 1 confuses the abbreviations for the two forms (GrN and GrA).

A long sequence of events is now identifiable as a result of these excavations. Firstly, the area was used to some extent before the construction of the monument, and some Neolithic sherds and radiocarbon dates indicate activity c. 3800-3700 BC. A Mesolithic chert flake was also found, though this single item can hardly be used to indicate that the site was a ';sacred place'; (page 246) for hunter-gatherers, and it is more mundanely interpreted by lithics specialist Graeme Warren in Appendix 8 as indicating some kind of Mesolithic activity, or the use of a Mesolithic artefact as an heirloom.

The construction and original use of the tomb has now been radiocarbon dated to 3350-3100 BC. It is estimated that the tomb contained more than 300 burials including 63 from the three primary cists built against the outside of the chamber. As at Fourknocks, many of the unburnt burials were infants or children; however this part of the report is not altogether satisfactory due to the fact that the anatomist was unable to complete it due to ill health. A number of cremations placed around the perimeter of the mound, were shown by radiocarbon dating to be contemporary with the burials in the tomb. The tomb and cists also yielded an amazing range of artefacts, including two intact Carrrowkeel pots (protected in the cists); bone and antler pins; balls, beads and pendants, the latter made from unusual stones such as serpentine, while the balls and beads were from more mundane materials. A collection of unusual bone tubes probably formed a pair of long necklaces.

There are some indications of later Neolithic activity around the mound, in the form of linear palisades and a ring of fire pits. The author is hesitant to assign the large oval enclosure detected recently through Discovery Programme gradiometry programme (Fenwick, J. and Newman, C. 2002. Geomagnetic survey on the Hill of Tara, Co. Meath, 1998-9. Discovery Programme Reports 6, 1-17) to this period, and underplays the use of the site in the earlier third millennium BC, claiming (page 244) that there was no ';aggiornamento'; as in the Boyne Valley at this time.

Be that as it may, the contrast with the Boyne Valley sites is certainly remarkable for the next phase of activity at the mound, when a series of c. 25-30 burials were inserted into the tomb chamber or its covering clay mantle. These were accompanied by both bowls (3750-3600 BP) and various forms of vases (3750-3500/3400 BP), or by collared urns (3570-3360 BP), as well as a small range of other material such as razors, awls and a magnificent battle-axe.

Unfortunately it proved impossible to reconcile the terminology used for the Early Bronze Age pottery between the main report and the discussion in the appendix dealing with radiocarbon dates. The main report uses the older term ';Food Vessel';, while the appendix employs the more recent nomenclature, such as bowls, vases, vase urns, and encrusted urns. There are inconsistencies even within the main report: the pot from Burial 33 is described both as a vase Food Vessel and as a Food Vessel of bowl/vase form on page 185. It is called a vase Food Vessel in Appendix 2, a Bowl/vase Food Vessel in both the general list of artefacts (Appendix 4) and in Table 18, while it is described as a tripartite bowl in the radiocarbon Appendix (my italics). One of the pots from Burial 38 is classed as a vase Food Vessel in the report and as a cord decorated urn in Appendix 7. The well-known inhumation burial of a young male accompanied by a range of exotic beads (faience, jet, amber and bronze), a razor and probable awl, but no pottery, published by Ó Ríordáin in 1955 has now been radiocarbon dated to 1750-1500 BC and was thus the last burial inserted into the mound.

In bringing all this material to publication, the author had an unenviable task, inheriting the less than perfect archive of an old excavation, and with some of the paperwork, artefacts and human remains lost, or being recovered only as the study advanced. An important field drawing was located after the report had been edited and had to be added as Appendix 10. Sensibly, O'Sullivan has identified those areas of the archive and record where information is lacking or unclear.

For the most part the report is easy to follow, no small achievement under the circumstances. Unfortunately, the gremlins have attacked what would otherwise have been a very useful concordance list (Appendix 4), and the figure numbers have slipped forward 2-4 numbers; a random check of c. 12 figure numbers listed found them to be all incorrect. The illustrations are of a uniformly high standard, especially the drawings and photographs of the artefacts; old black and white photographs are also excellent, and though unattributed, are, perhaps, Jim Bambury's work.

Dr O'Sullivan has grappled valiantly with the unenviable task of pulling all this material into shape, and has succeeded in presenting us with as clear a picture as possible under the circumstances. There is little or no discussion, but at least we now have a basic document from which further research at Tara can proceed.

Elizabeth Shee Twohig

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Decorated stone, orthostat L2 by Ursula Mattenberger from Duma na nGiall (The Mound of the Hostages)

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Newgrange

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Hill of Tara

| Fourknocks

| Loughcrew

| More Places

| Labyrinths

| Local Info

| Art Works

| Articles

| Images

| Books

| Links

| Boyne Valley Tours

| Contact