The sunrise around Samhain in early November aligns with the passage of the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara, allowing light to enter the chamber and illuminate its interior. This alignment marks Samhain as a significant moment in the prehistoric calendar. Samhain falls at the cross quarter of the astronomical year, positioned midway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice and signals a seasonal threshold rather than a precise solar turning point. The illumination of the chamber at this time suggests that these transitional moments held particular importance for the Neolithic communities who shaped the ritual landscape of Tara.

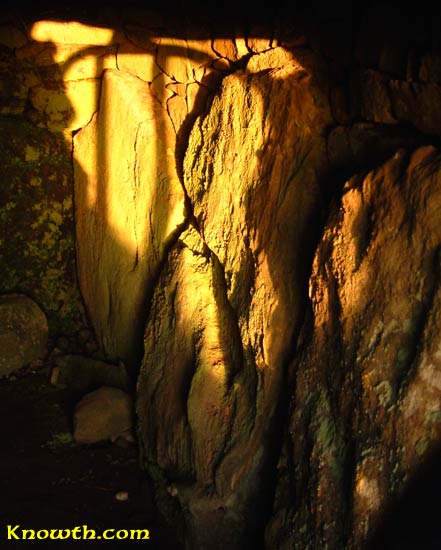

The photograph of the Samhain sunrise was taken on the 13th of November, around a week after the cross quarter day. By this point in the solar cycle, the position of the rising sun has shifted slightly, so the light enters the passage at a different angle, illuminating the side of the chamber rather than reaching the backstone. The parallel lines visible in the image are not prehistoric features but shadows cast by the iron gate at the entrance to the mound as the low morning sun passes through it.

Samhain and its associations with the Hill of Tara

Samhain marks one of the most important turning points in the ancient Irish year. Celebrated around the beginning of November, it signalled the end of the harvest and the start of winter. In early Irish tradition, this was not simply a seasonal change but the beginning of the new year itself, a moment when order was reset and the boundary between worlds was thought to thin. Among the many places associated with Samhain, the Hill of Tara holds a particularly strong and enduring connection.Samhain in early Irish tradition

Samhain was a liminal festival, a time between light and darkness, life and death, summer and winter. Livestock were brought in from pasture, surplus animals were slaughtered, and communities gathered to mark the close of the agricultural cycle. It was also believed to be a time when the Otherworld was closer, allowing spirits, ancestors, and supernatural beings to move more freely among the living. Early medieval texts repeatedly describe Samhain as a moment of danger and opportunity, when kingship could be challenged, taboos tested, and fate reshaped.

Lia Fáil in the Samhain sunrise, now standing on the King's Seat or Forrad, the stone once stood in front of the entrance to the Mound of Hostages

Tara as a royal and ritual centre

The Hill of Tara was not a single monument but a ceremonial landscape, long associated with sovereignty, law, and kingship. By the early medieval period, it was regarded as the symbolic seat of the High Kings of Ireland, even if real political power shifted elsewhere over time. Tara’s importance lay as much in ritual authority as in physical control. Seasonal assemblies, legal proclamations, and royal inaugurations were tied to the calendar, and Samhain stood out as one of the key moments when the relationship between king, land, and people was reaffirmed.Samhain and Royal Power at Tara

Early Irish literature often associates Samhain with moments of danger and transformation at royal centres such as Tara. Several narratives describe supernatural visitors arriving at Tara on Samhain night to challenge or threaten the king and his household, reflecting a belief that the boundary between worlds was especially fragile at this time of year. Samhain was therefore seen as a period of heightened vulnerability and power, when a king’s ability to maintain order and protect his people was a measure of his harmony with the land.The Mound of the Hostages and the Samhain sunrise

One of the strongest physical links between Samhain and Tara is found at the Neolithic passage tomb known as the Mound of the Hostages. This monument dates to around 3000 BCE, long before the later kings of Tara, yet it remained central to the site’s meaning for millennia. The passage of the tomb is aligned so that the rising sun illuminates the backstone around the time of Samhain and again at Imbolc in early February. This deliberate alignment suggests that these seasonal thresholds were already significant in the Neolithic period and continued to resonate in later tradition. By the time Tara became associated with kingship, Samhain was already embedded in the landscape itself.Kingship, renewal, and the turning year

Samhain was a moment of judgement. A king who failed to uphold justice or prosperity risked disaster in the coming year. Tales set at Tara often use Samhain as the stage for challenges to authority, otherworldly demands, or revelations of hidden truths. In this sense, Samhain at Tara was about renewal as much as fear. It marked the end of one cycle and the testing of whether another could begin in balance.A landscape shaped by time and memory

What makes the Hill of Tara unique is the layering of meaning across thousands of years. Neolithic monuments, Iron Age earthworks, and early medieval tradition all converge on the same hill. Samhain acts as a thread linking these periods, a seasonal moment that retained its power even as belief systems changed.Today, Tara is quieter, but the associations remain. Standing on the hill in late autumn, with shortening days and low light, it is easy to understand why Samhain, Tara, and the idea of the turning year became so closely bound together in the Irish imagination.

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Newgrange

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Hill of Tara

| Fourknocks

| Loughcrew

| More Places

| Labyrinths

| Local Info

| Art Works

| Articles

| Images

| Books

| Links

| Boyne Valley Tours

| Contact